A simple study in visual perception—an exploration of how a plain hexagon can evolve into the illusion of a cube. Through precise geometry and controlled form blending, static lines awaken into rhythm and volume, giving rise to a subtle sense of depth and movement.

Constructing the Illusion

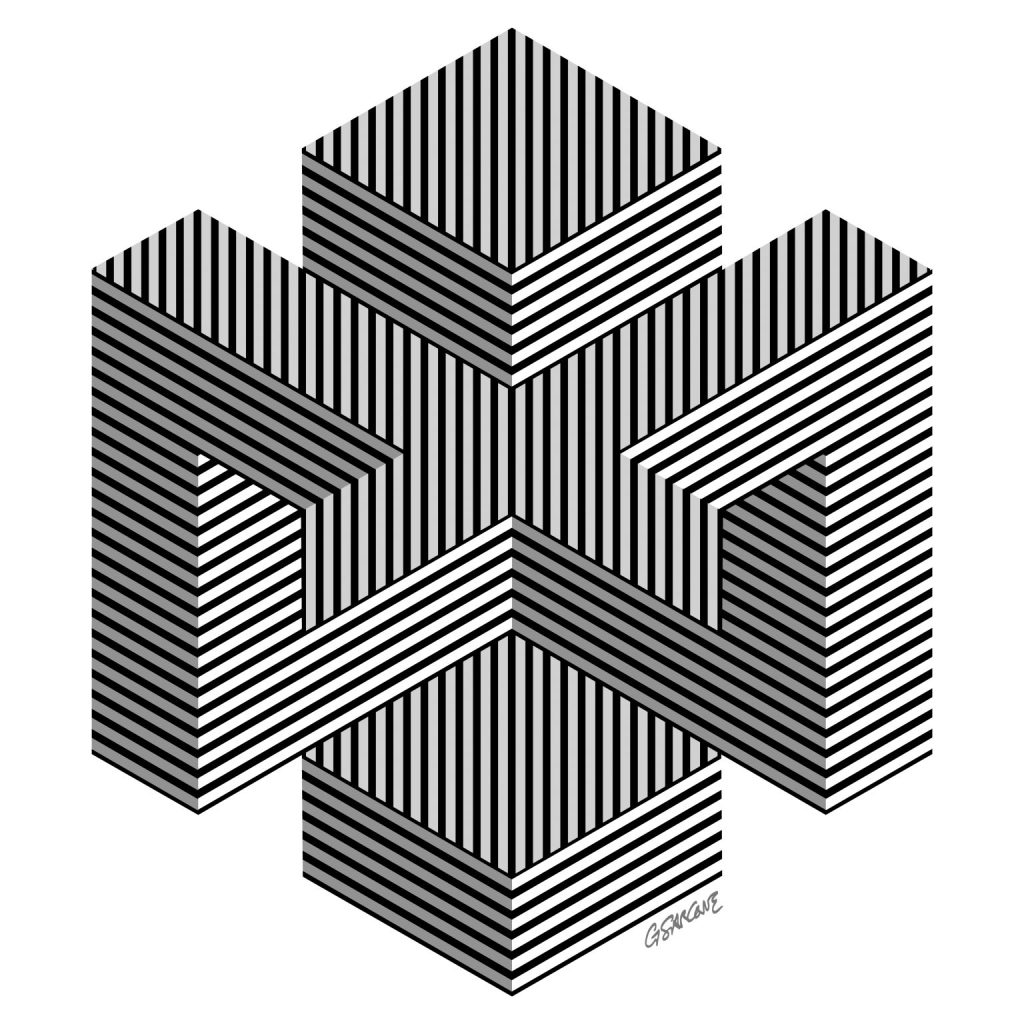

Fig. A — The Base Shape

Start with a regular hexagon. Divide it into three equal diamond shapes (rhombuses)—these represent the three visible faces of the cube. Each diamond has four equal sides: two acute angles (60°) and two obtuse angles (120°). Together, they form the geometric foundation of the cube.

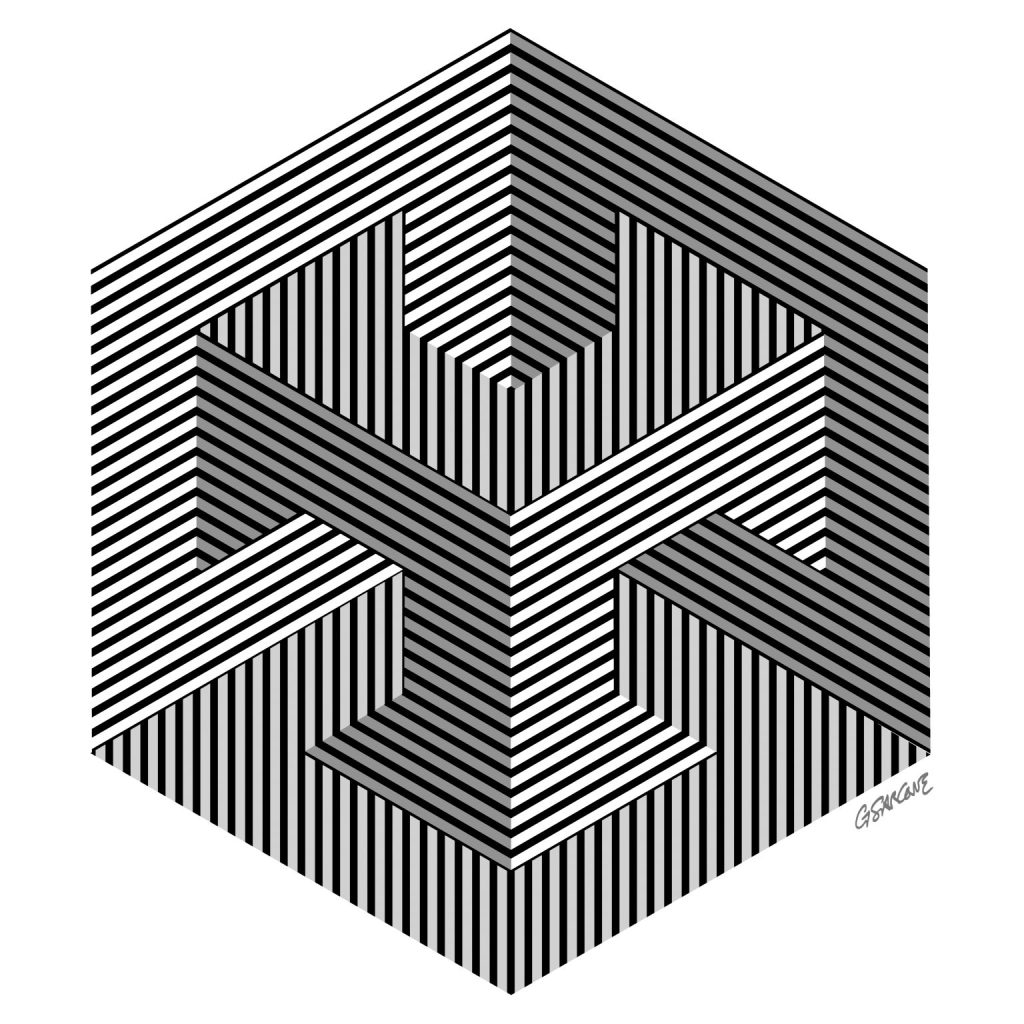

Fig. B — Building Volume with Shape Blends

In Illustrator, or any other vector software, use the Blend Tool to create a shape blend inside each diamond. Start with a small central circle and blend it toward the outer edge of the diamond. Adjust the number of blend steps to control how smooth or tight the transition appears. This process builds the cube’s apparent volume and visual tension. You’ll notice that the distance from corner to corner in the nested, diamond-like shapes is slightly greater than from side to side, creating subtle gaps that lead the eye to perceive an X across the surface.

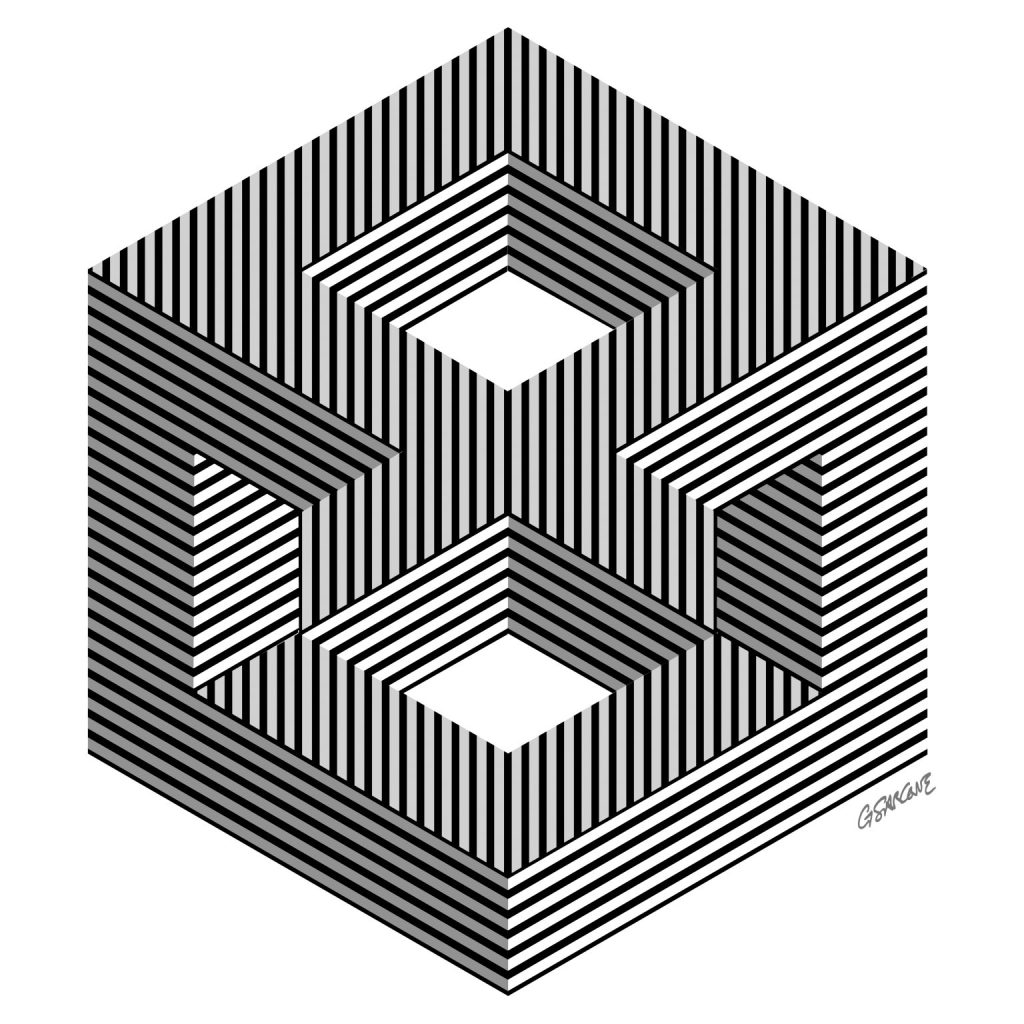

Fig. C — Perspective and Transformation

Distort slightly the hexagon to set the three diamonds in perspective. This step transforms the flat figure into a die-like cube, giving it spatial depth and presence.

Enhancing the Optical Effect

Next, add horizontal background lines and some color, as shown in the two examples in the image. You can also adjust the illusion by making the visible faces of the die appear slightly concave, as in the figure on the right. This effect is created by shifting the concentric, nested diamond shapes slightly off-center—the position of the central ellipse determines whether the die appears concave or convex.

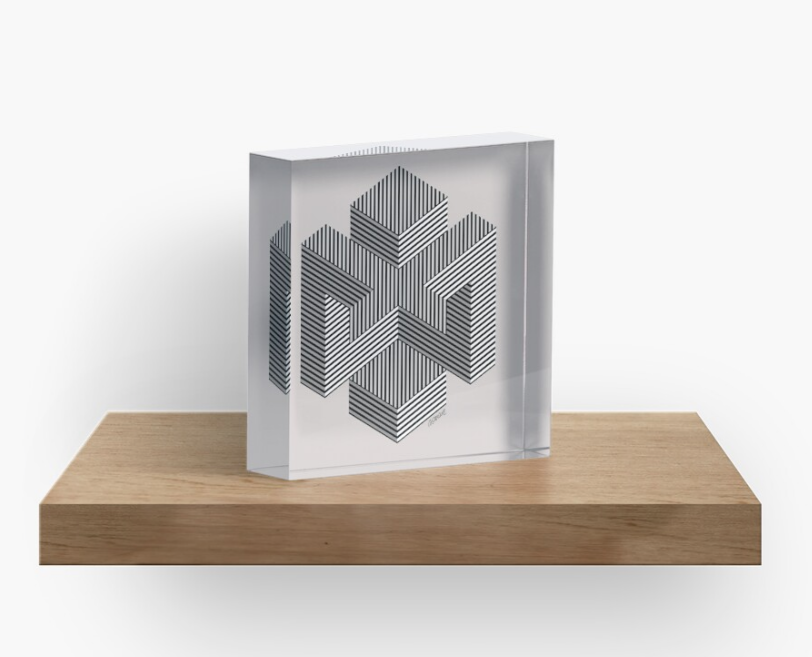

Below is the finished stage of the work. Curiously, the cube appears to hover, slide, and even emit a faint blue glow—though it remains entirely black and motionless.

Ananke’s Die is a study I began in 2010, a continuing exploration of how repetitive lines and geometric precision can trick the mind into sensing motion and color where none exist.

You can get Ananke’s Die as a fine art print or canvas, available in different sizes and finishes.

👉 Buy it here

Why Ananke’s Die

I titled this work Ananke’s Die after Ananke, the Greek goddess of necessity and fate.

The cube, a symbol of structure, represents order and control. Yet the three visible faces that seem to define its volume are an illusion—shifting and unstable.

Under the viewer’s gaze, the shape changes, its meaning shifts, yet the form remains.

This illusory die shows the balance between order, perception, and destiny, reminding us that what we think we control often exists within the unpredictable interplay of vision and inevitability.

This image also triggers multiple associations in a loop: hexagon, cube, die, chance, illusion, order, fate, contradiction. These connections show how perception mixes stability and randomness, revealing that what we see is shaped as much by the mind as by reality.