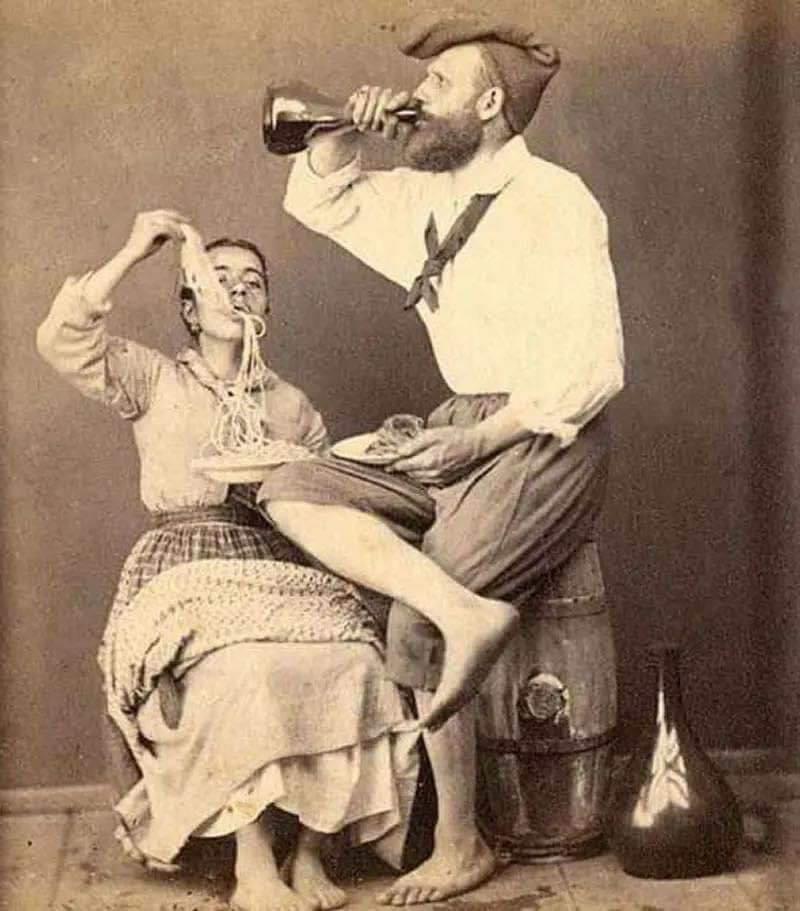

Images like the one below did not emerge as authentic snapshots of daily life, but as carefully staged performances. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a wave of photographers—from northern Europe and even northern Italy—descended upon Naples in search of the “picturesque” and the “exotic.” They were driven by the same Romantic and Orientalist impulses that had shaped the artistic imagination since the 18th century: a fascination with the “other” as a source of aesthetic and commercial consumption. To satisfy these expectations, they asked members of the working class to pose while eating spaghetti with their hands or drinking wine directly from the flask, creating scenes that conformed to a folkloric, almost theatrical narrative designed for foreign curiosity.

In reality, Neapolitans did not habitually eat spaghetti in this manner. While the very poorest—often lacking cutlery—might occasionally have done so, this was an exception rather than a rule. The subjects of these photographs were usually recruited precisely for their visibility as impoverished figures, their gestures carefully orchestrated, and their participation purchased with a few coins. Here, the camera did not document an everyday reality; it manufactured a tableau vivant, crystallizing a myth that would outlast the moment.

This visual fiction illustrates a broader sociological and philosophical pattern: the ways in which communities are reduced to caricature when mediated through the desires of outsiders. Naples, with its intricate social fabric, vibrant markets, and rich urban life, became a stage set for clichés—its complexity compressed into a singular, digestible image. In this sense, the photograph is not merely a representation but an act of authorship, shaping knowledge and perception as much as it pretends to capture it.

The legacy of these manufactured images endures. Modern media, advertising, and even social networks continue to freeze identities into simplified, performative snapshots. Stereotypes, once formed, acquire a durability that can eclipse lived experience, influencing perceptions across generations and reinforcing asymmetries of power between observer and observed.

The “spaghetti eater” is thus emblematic of a philosophical paradox inherent to photography: while the medium claims to reveal truth, it is equally capable of constructing fictions—fictions that, once disseminated, can appear more real than reality itself. In the intersection of image, expectation, and interpretation, we confront a cautionary truth: to look at a photograph is not merely to see, but to negotiate between truth, myth, and imagination.